John Geppert, professor of finance and director of assessment for the College of Business Administration (CBA), has a keen interest in student peer assessment of writing. Not only because the literature finds improved learning and critical thinking when students engage in the practice, but also because peer review may offer a way to include more writing practice in more courses.

However, he had three primary concerns:

- Is there a system that will manage the peer review process that is easy for students and instructors to use?

- Is peer feedback useful?

- To what degree do student evaluations of each other’s work vary from their instructor’s evaluations?

"We underestimate the benefits of short writing and we don’t do enough of it because of the grading burden."

- John Geppert, Professor of Finance and Director of Assessment, College of Business Administration

After all, if the system is too complex, faculty and students will reject the practice, and if student evaluations differ too greatly from their instructor’s then the value of their feedback is diminished.

With the availability of Canvas to university faculty came a new, built-in peer review system. Used heavily at the University of Central Florida, the second-largest university in the nation, it promised to be adequately robust to handle large class sizes at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Geppert put the system to the test with approximately 90 students in his FINA361 course by having them use Canvas for a single extended definition assignment where students explain a particular financial concept in detail for a lay audience.

To support their use of the system, Geppert supplied students with step-by-step directions for uploading their papers and for completing the peer reviews in Canvas. He followed up with students by emailing those who had not yet successfully uploaded a paper and for the small number of students who turned in their assignments late, Geppert manually assigned reviewers.

He also supplied students with a rubric and required them to give at least one comment about what was good about a paper and one clear suggestion for improvement. Geppert found most students took these tasks seriously and gave specific and useful feedback.

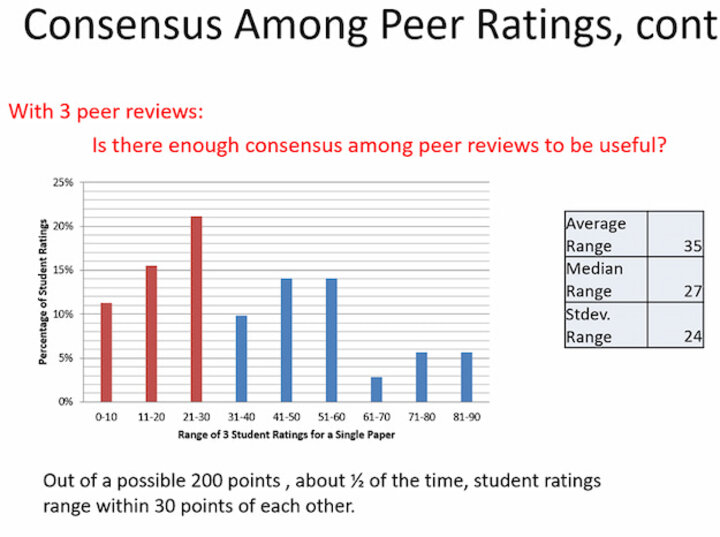

Of particular concern was the degree of consensus among peer ratings. On a scale of 200 points, the average peer rating was 168, or 84%. The standard deviation of peer rating was 19. The minimum peer rating was 97 and the maximum 196, so there was enough variance to ensure that students were not just rating everyone as “good.” Too little consensus would render feedback less useful, but Geppert found that about half the time, student ratings were within 30 points of each other which he considered close enough to be meaningful.

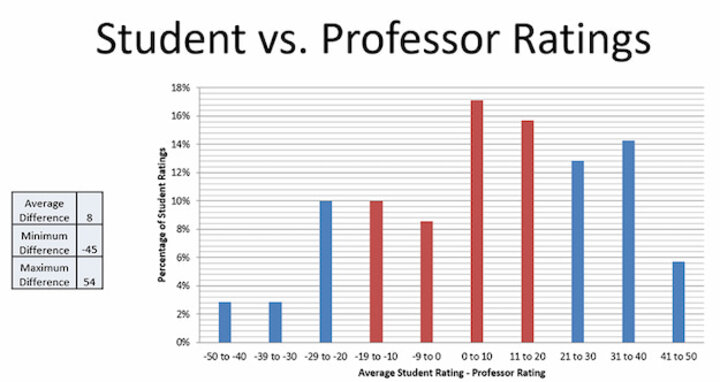

Finally, Geppert wanted to know how closely student ratings matched his own. He found that about half the time, ratings were within +/- 20 pts, and the average difference of 8 points indicated, at least in this course, students weren’t systematically easier or harder graders than the professor.

Geppert found many students made few changes to their initial draft submissions based on peer feedback. However, because he deducted points for not incorporating valid feedback, about half the students received lower grades on their final papers than they earned on their initial efforts. Geppert believes students would modify their behavior over time.

Geppert’s preliminary conclusions are as follows:

- Students learn the submission and review process in Canvas quickly

- Most students provided useful feedback to their peers

- Peer grading was sufficiently consistent as to be informative

- There was a 4% difference between the peer grade assigned versus the professor grade, with students grading easier.

Based on these initial findings, CBA moved ahead with using the Canvas peer review tool in a new large enrollment business writing course, BSAD220, with approximately 440 students. In an upcoming issue, we’ll follow up with the instructor in that course to find out how the tool worked and what lessons were learned.

He has also graciously shared his collection of references for student peer assessment of writing. These are available in .RIS format and may be imported into any reference management tool. Finally, Geppert had some important tips for using peer review of writing successfully:

- Use exemplars from actual students to help them understand its possible for them

- Keep the rubric globally focused, not a list of 25 things

- Advise students to “give an example of one thing that was unclear and how it could be made clear.”

- Discourage students from explaining WHY something is better or would be better. The “why” is best left to instructors.