Content

Humans have limited capacity to think about and process information at any single point in time. Performance suffers when doing multiple tasks simultaneously or performing a single task that requires multiple different unpracticed skills. The amount of information that an individual can process at one time is referred to as cognitive load.

On this page

Understanding Cognitive Load

An example that many of us have experienced is driving in a new area or through a particularly complicated situation and feeling the need to turn down the radio volume. It feels like watching the road and listening to music are unrelated behaviors, but they actually pull from the same pool of available cognitive resources. Under normal circumstances, the radio is a welcome addition and doesn’t interfere with our focus on driving, but when we’re searching for a specific house number or encountering dangerous driving conditions, the radio can quickly become a problematic distraction.

As the driving example demonstrates, it is easy for extraneous factors to impact performance, and the degree of impact is determined by specific aspects of the situation. When designing classroom learning experiences, it is important to think about all the different features that may impact student cognitive load since it is easy to become overwhelmed by complexity when trying to learn new tasks. Students generally learn most effectively when they can focus on one thing at a time, rather than trying to learn multiple cognitive tasks or skills at once.

As an instructor, it is important to recognize that your own expertise on the topic impacts your perception of how complex the task is for novices. The amount of cognitive resources required to complete a task gets lower as a person gains expertise, so faculty often underestimate the cognitive demand of tasks they ask students to complete (Nathan et al, 2001). Things that experts have come to think of as a single step in a process are actually a string of multiple steps, each requiring separate mastery. Breaking a task into smaller component parts and having students focus on mastering one new task or skill at a time allows students to learn more effectively.

The cognitive load imposed by a specific task will also vary greatly across students. Those that have previous exposure to the concepts will be less prone to cognitive overload than those that are completely new to what you’re teaching. Sometimes, a student may have a high level of understanding of the material but be distracted during an exam by the presence of other students or noises happening in the room. Other students may have anxiety about the difficulty of the exam and how it will impact their grade, which can impair their ability to complete the exam to the best of their abilities.

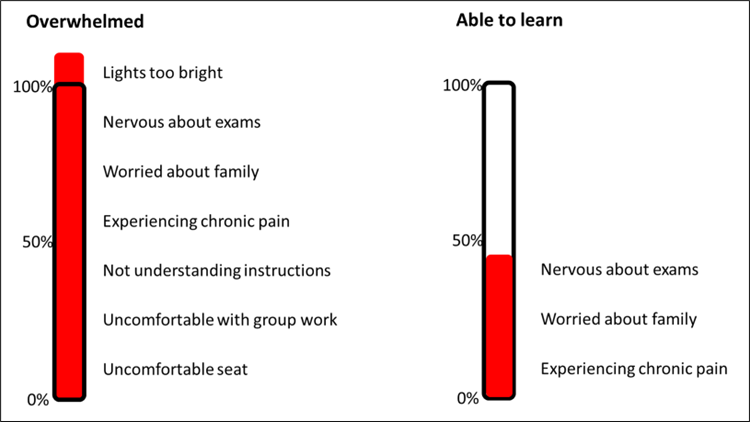

On the left, a red bar shows that when aspects of the classroom environment like uncomfortable lighting, being nervous about exams, and not understanding instructions are present, it can take up so much cognitive resource that students become overwhelmed. On the right, when those classroom elements are removed, the required cognitive resources is reduced, thus allowing students the capacity to learn.

Reducing cognitive load is effective for everyone's learning but is particularly important to improve learning for students who bring a higher level of cognitive load with them to the classroom (Le Cunff et al, 2022). For example, students who are neurodivergent may be more easily distracted by extraneous information or students who belong to minoritized groups might be coping with relational dynamics, including whether their classmates and professors think they belong in the classroom. As the diagram above shows, helping students reduce the cognitive load of classroom factors by providing clear instructions, dimming lights, providing multiple seating options, or letting them decide whether to work in a group can free up cognitive resources that help students better succeed in the classroom.

Strategies for reducing cognitive load

Course Design

- Give detailed, clear, and concise instructions for all assignments. Sometimes things that seem obvious to instructors are not clear to students. Laying out detailed expectations and instructions allows students to focus their cognitive energy on the learning goals of the assignment. It also reduces the number of student questions, saving instructor time. Grading rubrics can be a good way of summarizing information in a logical way.

- Scaffold class material by breaking it into smaller chunks. Take challenging concepts, skills, projects, and papers and break them up into smaller components and have students focus on one component at a time. Be sure to provide feedback on each component before moving on to more complex skills.

- Intentionally put the pieces together. When students learn individual skills or concepts, they won’t automatically know how they fit together. Be sure to build in time for them to practice skill and content integration separately from learning the individual pieces.

- Minimize barriers that may prevent students from getting help. Students who belong to marginalized groups are often hesitant to seek out help and even small barriers can prevent them from getting the help they need. Having your contact information readily available, using online scheduling systems such as Calendly, having a place on Canvas where students can ask questions, or having each student meet with you for 5-minutes at the beginning of the semester can help make it easier for students to reach out.

- Provide cognitive aids. Give students, or have students create, cognitive aids that help them learn the material more easily. This can include strategies such as concept maps, mnemonics, or activities that relate information to their lives.

Canvas

- Use a clear and consistent organizational structure. There are many ways you can organize your Canvas course, but a clear and consistent organization will reduce the cognitive resources that students use to navigate it. Whatever you choose, explain the organization to students so they can easily find everything since there is high variability across courses. One common structure is to have each week, chapter, or unit of content organized into a module. The module can start with an overview summarizing the learning objectives and activities for that module. Then include the rest of the material for the module, grouped in categories used throughout the entire course (for example, Read, Watch, Discuss, Demonstrate, etc.)

- Put the most valuable information on the home page. The home page is the first thing that students see, so use that space to make valuable information such as your contact information, course orientation information, and links to the modules readily available. Consider adding recent announcements to the home page so students see them.

- Have an orientation module that includes a welcome video. If you clearly explain how the class is structured, how to find course materials, and how to get help, then students can focus their cognitive resources on learning. Additionally, this can help students feel welcome and connected to the professor, which can reduce anxiety and increase feelings of academic belonging.

- Reduce clutter. Make the Canvas site as streamlined as possible and remove clutter. Customize your course navigation menu to only include items that students will use.

- Set due dates in Canvas. Enter due dates in Canvas so students can see reminders for upcoming assignments on their to do list. Make assignments with deadlines available as early as possible so students can plan their time in advance.

- Keep Canvas grades up to date. Students can focus more effectively on their learning when they know what areas they need to improve on and any misconceptions they might have get corrected quickly. If you use weighted grades, have the assignment groups set up correctly from the beginning of the semester.

- Complete a Canvas Scavenger Hunt. This activity is designed to help you better understand how students interact with your Canvas course. Either swap courses with another instructor or find a student unfamiliar with your course to complete the activity and provide feedback.

In Class

- Connect course content to students' emotions. Students learn more when they have some sort of emotional connection to the course material (Quinlan, 2016). Appealing to students' emotions and using story telling as a way of approaching course material can help students more easily form associations with newly learned content, thereby reducing cognitive load.

- Block class time in 15–30-minute chunks. For students to effectively learn, they need to be able to focus their attention on the course material and have time to process what they have learned. Blocking class time in 15–30-minute chunks and switching the type of activity that you have students working on allows students to maintain their focus more easily and provides space for students to process what they have learned.

- Make connections to previously learned information. People learn more effectively when they are connecting what they are learning to information that they already know (Quinlan, 2016). Encouraging students to relate class information to things they already know or connecting new concepts to information already learned in the course can help students learn more quickly and effectively.

- Provide time for students to think. Different people take different amounts of time to process information, and people learning new information often require more processing time than instructors expect. Ask reflection questions throughout the class time and give students a few minutes to think or write about the question before discussing it.

- Focus on the purpose of the activity. Identify the purpose and goals of a class activity and eliminate any unnecessary components or tasks. Streamline course content as much as possible to focus on the learning objectives.

- Avoid presenting competing textual and audio information. People have difficulty processing auditory and textual information at the same time, particularly if the information presented in each modality differs (Mayer & Moreno, 2003). When using both auditory and textual information in class, such as when giving a PowerPoint presentation, either have the text be an outline of what you are explaining or stop to give students time to read before verbally explaining the information.

Resources

- This web page provides a more detailed introduction to cognitive load theory and how it can be useful for instructors. The book Minds Online by Michelle D. Miller discusses the cognitive science of how humans learn and what that means for online learning and the use of digital course materials.

References

Le Cunff, A. L., Dommett, E., & Giampietro, V. (2022). Supporting neurodiversity in online education: A systemic review. In McKenzie, S. P., Arulkadacham, L., Chung, J., & Aziz, Z. (Eds.) The future of online education: Advancements in learning and instruction. Nova.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43-52.

Nathan, M. J., Alibali, M. W., & Koedinger, K. R. (2001). Expert blind spot: When content knowledge & pedagogical content knowledge collide. Institute of Cognitive Science Technical Report. University of Colorado Boulder.

Quinlan, K. M. (2016). How emotion matters in four key relationships in teaching and learning in higher education. College Teaching, 64(3), 101-111. DOI: 10.1080/87567555.2015.1088818