Accessibility and Universal Design for Learning

Creating accessible digital content allows everyone, including students with disabilities, to participate in the learning experience more fully. Accessibility unlocks features in our technologies that some people need, and others often appreciate. For example, when captions are added to a video, it gives access to learners with hearing impairments. But the captions are also very helpful for multilingual learners, students studying in loud spaces, or wanting to pinpoint the spot they need in a lecture by searching the captions. When accessibility is implemented, it supports a wide range of learners.

Opportunity to participate in digital accessibility research

A team from the Center for Transformative Teaching is conducting a research study examining the effectiveness of the Digital Accessibility training in the Bridge portal at UNL. Anyone who has completed the training is eligible to participate in the study.

Accessibility Links

Accessibility is part of a larger framework called Universal Design for Learning (UDL). The UDL framework is designed to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. UDL includes accessibility measures and considers ways to address a wider range of barriers, such as motivation, background knowledge, and executive function. This framework focuses on providing different types of materials, engaging students using active learning strategies, and assessing learning using many types of assessments.

Teaching and Generative Artificial Intelligence like ChatGPT

This CTT resource introduces faculty to A.I. and provides information about common questions around policies and adapting instruction. We encourage faculty at UNL to contact us at ctt@unl.edu if they would like to explore the capabilities of ChatGPT4 or other AIs without creating accounts.

Prompt Library for Teaching & Learning

Ethan Mollick and Lilach Mollick have created a collection of prompts that can aid instructors and students. These are extensive prompts worth reading to better understand the capacity of AI to perform more sophisticated work, as well as the knowledge and expertise needed to create such a prompt.Tom's Guide Succinctly Summarizes Current ChatGPT Alternatives

In this overview, the author highlights the capabilities of generative AI's offering capabilities on par with ChatGPT. Each has specific strengths and weaknesses. However, one area not addressed is how user input is used. For example, Meta uses the information that people share to improve their products "and for other purposes." Consequently, as with any new technology tool, read the privacy information before engaging with the technology.Classroom examples added to AI Exchange

In these classroom examples, Brian Wilson explains how he uses ChatGPT to help him manage lively discussions while Samantha Fairclough shows the many AI tools she is trying in her entrepreneurship courses, and Erin Bauer outlines her assignment where students collaborate with AI to critique a journal article.

AI and Information Literacy Canvas module available to UNL instructors

A new module, “AI and Information Literacy” is now available in the Canvas Commons. This module is written for students to help them learn about AI tools such as ChatGPT, Bing AI, and DALL-E and strategies for evaluating and citing the outputs created by them. Insert this module into your course and use it as-is or modify it to suit your teaching and learning goals and course policies. Content includes short videos, reading, completing short quizzes, and activities.

Once completed, students will be able to evaluate how to use AI-based tools responsibly in their academic work. Learning outcomes include:

- Explain generally how AI-based tools work as well as their benefits and risks

- Recognize when AI gives inaccurate or misleading answers, and fact-check AI output

- Cite AI-generated work

- Begin exploring creative ways to use these tools

This CC-licensed module was adapted by the UNL Libraries and the CTT and originally created by the University of Maryland.

To add the module to your course, search the Commons for “AI and information literacy” and select “Import/Download”.

Questions?

Contact Melissa Gomis (melissa.gomis@unl.edu) or an instructional designer assigned to your college.

CTT launches AI Exchange

AI Exchange is a blog aiming to support discussion at UNL about the use of AI in teaching and learning. It will contain articles, essays, tutorials, as well as article summaries and reviews.

This month we’re kicking off the blog with “Questions Around the Ethical Use of AI in the Classroom,” an article by Rachel Azima and Amy Ort. Additionally, Nate Pindell shares the process and prompts he used with ChatGPT to generate a rubric. He also outlines how he used ChatGPT to quickly create a useful resource that he was unable to find online, and which would have taken a fair amount of time to create from scratch.

Increasing access and improving user interfaces

August kicks off with significant updates and announcements in A.I. Most notable are OpenAI’s prompt assist tools that will help faculty and students make more effective use of ChatGPT by guiding queries, suggesting follow-up questions, and offering keyboard shortcuts for power users. Additionally, OpenAI has made ChatGPT4 the default for paid users and suspended its A.I. detection tool used to detect ChatGPT generated content for being unreliable. The company plans to revise and re-release.

Other developments include the rapid release of new A.I.s and their widening availability. LLAMA 2, a chatbot for simple requests and conversations, has been released by Meta AI, is available for research, and commercial use. Other companies' embrace of A.I., such as Adobe and Autodesk, point to further specialization and integration with the applications students and faculty use daily. Faculty may begin to see more news of discipline specific A.I.’s in coming months.

Quick Start Resources

- Developing Course Policies

-

- Three types of policies and several examples

- Miron et al. (2023). Supporting Academic Integrity: Ethical Uses of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education Information Sheet (PDF). This resource provides guidance on how to communicate assessment expectations to students and what aspects should be considered when "cognitive offloading tools" are employed or available.

- Specific Examples of using A.I. as part of teaching

-

- Hendriksen, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Bing: A practical guide for social science and management studies. Google Docs.

- Nirantzi et al. (2023) 100+ Creative Ideas to use AI in Education. Creative Commons. Each slide in this presentation gives an example of how instructors or students are using AI to teach and learn.

- Alby, C. (n.d)ChatGPT: Understanding the new landscape and short-term solutions.Google Docs. This resource uses "problem/suggestions" format that may help address many initial questions.

- D’Agostino, S. (2023, January 12). ChatGPT Advice Academics Can Use Now. Inside Higher Ed.

- A more extensive article in which 11 academics propose ideas for “harnessing the potential and averting the risks” of AI technology in the classroom.

- Mills, A. (n.d.). AI Text Generators: Sources to Stimulate Discussion among Teachers. Google Docs.

- A large collection of resources and articles sorted into several categories among which are “Sample Academic Integrity Statements about Text Generators” and “Student Perspectives and Marketing to Students” along with “Understanding AI Text Generators/Large Language Models.”

Teaching Support Network

Although rewarding, teaching is complicated and often challenging. What works for one instructor in one context may not work in another. This means that it may helpful to foster a diverse support community as you search for the right approaches in your own context. The CTT's Instructional Designers have a valuable breadth of experiences and awareness of teaching research to serve as a foundation for your teaching support. You may also appreciate turning to peer instructors to dig deeper into specific teaching challenges and hear some new approaches. The following individuals have put significant effort into reflecting on their teaching practices and have agreed to provide peer teaching support. Additionally, if you would like to make use of the peer observation process, consider one of these instructors. Please contact the individuals below directly if you would like to talk about a specific aspect of teaching.

Jena Asgarpoor

Professor of Practice & MEM Director, Durham School of Architectural Engineering and Construction

Teaching Experience: 32 years

Format: Asynchronous web-based, engineering management, quality management, operations and management science

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Online Teaching

Passion for student success. Partnering with the students in their learning journey. Responsiveness and empathy. Letting students co-create their learning and educational experience

Erin Bauer

Graduate Lecturer, Entomology

Teaching Experience: 8 years

Online education (grads and undergrads); developing creative assessments

Key Interests: High-Enrollment Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Online Teaching, Experiential Learning

In my position as Graduate Lecturer in the Entomology Department, I teach several different online undergraduate and/or graduate classes, including three Forensic Entomology related courses, Insect Biology, IPM in Sensitive Environments, and an upcoming Cultural Entomology course. I also coordinate student Independent Studies and capstone MS Projects.

Taking online classes and TAing as a MS student were very positive experiences for me, and these really introduced me to all sides of online education…learning a LMS and submitting my own tests or papers through that; corresponding with other students; and designing or grading assignments. I’ve had the opportunity to refine different approaches and apply what I’ve learned to my own online teaching.

What I have discovered through teaching for several years is that ensuring successful student learning in a virtual environment can be even more critical than in a physical classroom. Through the very nature of distance courses, students are aware that they will likely not see the instructor in person, and that they need to have the technological resources and ability to complete their coursework online. The instructor also knows they need to connect and interact in a way that ensures students will still find them approachable.

With these things in mind, my approach is to address the unique characteristics of online education in a way that will most benefit students. This may include developing a syllabus that lays out all significant expectations of the course clearly and regularly updating students on the Announcements board or through group emails when a new lecture has been posted or that tests or assignments are due. It’s also helpful giving positive feedback about how students answered or addressed an assignment. In addition, I frequently remind students that they can email me at any time, as this is the prime communication method in online courses.

An advantage to online education is that the ease of document exchange (assignments submitted through Canvas or email) can allow me to be more flexible with students than a teacher might be in a normal classroom setting. For example, I may encourage students to correct mistakes they made on an assignment, resubmit, and gain more credit. Students have commented about how they appreciate the opportunity to make improvements.

Student learning styles in online courses is likely to be varied. This has a lot to do with the demographics of the students in these programs. Many online students are non-traditional (usually in 30s-50s age range), working full time or in the military, living in another state or country, and able to take limited classes a semester. These students may have been away from college for a while and be unfamiliar with online education but wish to take this format because of its flexibility and their geographical location. Learning styles of these students tend to be more traditional, and they may require more help from the instructor. Younger students often take online classes for convenience and may be more familiar with technological tools. Having a mix of students at different levels in one course can be challenging, but I've found that good communication between instructor and student is key in reducing any obstacles that may arise.

I also like to encourage creativity in my students. I offer assignments where they can express themselves (such as stories or artwork) or do something different (e.g., play an educational game). Overall, while the understanding of basic facts is essential to comprehending a subject, true learning requires the next steps of analysis and synthesis. By offering a variety of assignments and instructional formats (papers, videos, narrated lectures, etc.) and providing significant feedback, I feel students can make the jump from simple factual knowledge to applied knowledge that enhances learning and contributes to their field of study.

Ian Borden

Associate Professor of Theatre Studies and Performance, Theatre Arts & Film

Teaching Experience: 23 years

History of Fine Arts and its Effect on Society, Renaissance Theatre, Performance and Stage Movement (Certified Stage Combat Teacher), Online Teaching

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Lecture-Based Teaching, Encouraging Academic Honesty, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Online Teaching, Group Work, Creating New Classes

One of the best things I ever heard about teaching came from my first acting teacher. He noted that "we are all on the same road, he's just further along on it." That's a very humble approach that I've tried to emulate by breaking down barriers between the instructor and the students.

Another great thing I heard came in my first year as a faculty member. I was complaining to my colleague about my students, and she simply said, "Ian, we were the good students." Since then I've tried to make sure that my teaching reaches every student in my class, especially those that are struggling with how to be a university student. It's a set of skills that many students do not have in terms of preparation, that is exacerbated without family support. That's the teaching that happens outside of the ordinary classroom environment.

I have also been involved in a lot of diversity development for UNL over the last five years, and as someone who frequently teaches classes to students from all parts of the university, I've realized how important it is to be willing to change. The biggest lesson there was that if the canon isn't working, change the canon. Although it can be a little bit scary to move away from the ways that I was taught, I found that re-thinking what was canonical to be the simplest and most effective means of reaching more of my students.

Chad Brassil

Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences

Teaching Experience: 19 years

Inclusive Pedagogy; Active Learning; Recorded Lectures

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, Lab Teaching, High-Enrollment Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Lecture-Based Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Group Work

My current area of interest is using data to inform inclusive teaching practices. On of the strategies most supported by evidence is active learning, which I have been in a continual effort to incorporate into my large enrollment courses. I've benefited a number of times from co-teaching experiences, learning from each colleague.

Brian Couch

Associate Professor, School of Biological Sciences

Teaching Experience: 11 years

Programmatic assessment, assessment motivation, question formats, formative assessment, and assessing science practices

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching

Teaching LIFE 120 has given me familiarity with the logistics of running a large, introductory course. Some unique aspects of this course include in-class clicker-type activities, multiple-true-false questions, study contracts, and teaching assistants.

Cynthia Cress

Associate Professor, Special Education & Communication Disorders

Teaching Experience: 29 years

Language Development & Disorders, Communication Assessment & Intervention, Autism, Early Intervention, Counseling/behavior management

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Experiential Learning, Group Work

I prioritize individual engagement with students even in large undergraduate classes and this is reflected in my course evaluations of students feeling valued and included in courses. All my undergrad and grad courses incorporate multiple examples of applications of course content, both during class and in out-of-class assignments. I value critical thinking activities to challenge students in achievable ways to help them discover that they can address the unknown that will occur in their professional lives.

My effectiveness in engaging meaningfully with undergraduate students is partly reflected in 8 Parent's Recognition Awards so far. I was also honored with the CEHS Distinguished Teaching award in 2007 to reflect overall quality and effectiveness of teaching. My skills at accommodating change and challenge were noted in being asked to present workshops on hybrid teaching strategies in 2020 after rapidly recalibrating to include unfamiliar online teaching strategies from basic in-person blackboard and overhead teaching prior to that point. I have served as teaching mentor for multiple faculty within SECD and enjoy stepping into someone else's teaching style to help them maximize the effectiveness of their own teaching strategies.

I firmly support the individualization of faculty as well as student learning styles and facilitate that in whatever ways I can. I also continue to evaluate and modify my own teaching strategies based on peer and student input and have been willing and able to entirely change models of instruction, given our recent departmental innovation of team teaching courses that were previously individually taught. I enjoy learning from my colleagues as well as students and never consider my courses or teaching as "done".

Jenny Dauer

Associate Director for Undergraduate Education in SNR, Associate Professor in Science Literacy, School of Natural Resources

Teaching Experience: 24 years

Active learning, cooperative learning, inclusive teaching, science literacy, issues-based teaching, experiential learning

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Experiential Learning, Group Work

I'm the lead instructor of SCIL 101: Science and Decision-making for a Complex World. The course is based in skill development over specific content. The course relies on teaching techniques in active learning, cooperative learning, learning for "transfer," inclusive teaching, issues-based instruction, theories of motivation, etc.

Amanda Gonzales

Associate Professor of Practice, Accountancy

Teaching Experience: 10 years

Facilitating Effective Team Projects

Key Interests: Group Work

I seek to inspire my students toward lifelong journeys of self-discovery, growth, and confidence in pursuing opportunities that are consistent with their values, priorities, and talents. I'm currently investigating whether students’ explicit recall of their individual and collective strengths as part of team charter development enhances measures of team effectiveness such as team cohesion, member satisfaction, and performance, while also considering best practices for team projects more broadly. I've also explored and implemented backwards course design, student choice within individual projects, and early assessment of prerequisite knowledge.

Chris Graves

Assistant Professor, Editorial (News-Editorial)

Teaching Experience: 3 years

Experiential learning, Student engagement -- especially in long classes (2+ hours). Organization of Canvas and teaching materials. Group work in class. Facilitation class discussion.

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Encouraging Academic Honesty, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Experiential Learning, Group Work

Why do I teach? For the same reason I became a journalist. I am a curiosity-addict. I believe there is no end to improvement. I seek, question and wonder how I might be better, how I might do better. As a teacher, I work to engage and inspire students to be question askers and knowledge seekers.

Further, I believe I am on a journey with my students and with the dawn of each semester we enter into a learning relationship. I view the classroom as a place for students’ brains to hurt and for their hearts to swell. It should also be a place that is supportive, empathetic and safe as they learn to practice curiosity. The work ought to be challenging and meaningful and complicated and difficult. I want my classroom to be where empathy and understanding and an appreciation for differences is not only encouraged, but modeled — we learn, too, by watching and then replicating. The classroom, and certainly my actions as the instructor, should be a model for what we want for our larger communities.

I bring three core principles into the classroom and into my teaching: Learning by doing, practicing curiosity and the art of listening.

I view failure as an important step toward success. In practice, that means I spend most classroom time on exercises (both individual and group) where students apply/practice concepts and then outside of class continue to work on those skills. Students are encouraged to resubmit written work in all they do. This means a ton of grading and re-grading, but their work continues to improve as does their self-esteem.

I taught for nearly five years as an adjunct instructor at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. I am entering my third year of full-time teaching at UNL. I teach primarily beginning reporting, writing and editing courses. This past year, I became the lead instructor for a 400-level, international journalism program and I am in the midst of learning to evaluate my teaching at a higher level. I teach editing, reporting, writing as well trauma-informed reporting practices, solutions journalism and overcoming bias in reporting.

Andrew Hanna

Assistant Professor of Practice, Management

Teaching Experience: 5 years

Entrepreneurship, Management (Organizational Behavior, Business Psychology)

Key Interests: High-Enrollment Teaching, Experiential Learning, Teaching with Technology, Lecture-Based Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom

As an instructor in the UNL College of Business, Andrew teaches MNGT 360: Managing behavior in organizations, ENTR 421: Identifying and exploring entrepreneurial opportunities, ENTR 321: Entrepreneurship and innovation in organizations, MNGT 398: Global Startup Communities: Entrepreneurship in Rwanda, MNGT 361: Human resource management, and MNGT 475: Business strategies. He currently serves as a faculty advisor for the Startups UNL entrepreneurship student organization and annually leads an entrepreneurship-focused study abroad to Kigali, Rwanda, where students explore the entrepreneurial opportunities of emerging economies. As an instructor, Andrew's main focus is on fostering a culture of radical transparency in the classroom; an idea he maintains is the key to the great experiences his students have reported in his past classes. As a doctoral student and faculty member, Andrew has received multiple nominations for the College of Business teaching award, winning the award in 2021.

Deryl Hatch-Tocaimaza

Associate Professor, Educational Administration

Teaching Experience: 16 years

Asynchronous learning communities, graduate education, mentoring, writing as a process

Key Interests: Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Online Teaching

Dr. Hatch-Tocaimaza teaches courses in the areas of higher education administration, community college leadership, and research methods. With these programs offered online at UNL, his teaching and mentoring has been primarily accomplished at a distance. This has led Dr. Hatch-Tocaimaza to develop innovative methods to foster virtual learning communities and techniques for reflective practice.

An area of exploration is in techniques for teaching writing as a process, and the formation of a researcher identity and competencies among graduate students who are also working professionals. Dr. Hatch-Tocaimaza received the 2019 Outstanding Teaching Award from the UNL College of Education and Human Sciences.

Courtney Hillebrecht

Professor; Hitchcock Family Chair in Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, Political Science

Teaching Experience: 19 years

Inclusive excellence, large-enrollment lectures and student engagement, balancing teaching with research and administrative demands

Key Interests: Inclusive Teaching, High-Enrollment Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Balancing Teaching with Other Work

I teach a variety of courses in international relations, international law, human rights and comparative politics. My teaching philosophy is simple: I seek to challenge students to think critically and to engage with the material we discuss in class as well as contemporary politics. I place a large emphasis on improving my students’ writing, analytic, research and presentational skills and helping them understand the connections between international politics and their daily lives. I often rely on simulations to help students sharpen their skills and link concepts with practice. I center all of my teaching on the principles of inclusive excellence.

Libby Jones

Professor & Assoc. Chair for Undergraduate Programs, Civil Engineering

Teaching Experience: 26 years

Alternative grading, active learning, flipped courses

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Teaching with Technology, Inclusive Teaching

I’m a Professor in the Civil & Environmental Engineering Department where I also serve as the Associate Chair for Undergraduate Programs.

My approach to teaching is to focus on student learning and student success. I want students in my courses to finish courses with me having learned, having had an opportunity to demonstrate their learning achievements, and believing their learning achievements were fairly evaluated. I also want them to be more curious about the subject and continue to learn about it even if they never take another formal course in it. I am always working to improve the success of my students.

My teaching experiences range from large first-year courses, to required discipline courses, to small graduate seminar courses. I’ve taught traditional in-person courses, courses offered by interactive TV between Lincoln & Omaha, and more recently, an asynchronous online course offered in the January pre-session. I continue to modify my courses to make them more active and more inclusive. Things I’ve tried and found useful include think-pair-share, in-class polling, and peer instruction. I continue to develop my courses so that as a class, we spend the limited in-class time working on more difficult concepts instead me lecturing on more basic material that can be covered in through pre-class readings and other activities. Some might refer to this as a “flipped course”. More recently, I’ve also worked to make my classes more inclusive by changing how I assess student learning, how I grade, and my course policies. Other things I’m also working to improve in my classes include student reflection, experiential learning, and student agency. Beyond my courses, I’m also leading our department’s effort to revise our curriculum to better prepare our students to be successful engineers throughout their careers. We are doing this by incorporating more experiential learning throughout all four years.

I’ve participated in many faculty development initiatives at UNL including the Faculty-led Inquiry into Reflective and Scholarly Teaching (FIRST) program, the CTT’s Reflective Practitioner Program, the College of Engineering’s Teaching Fellow Program, and the Faculty Fellows for Student Success Program run by Amy Goodburn.

David Karle

Associate Professor and Director of Architecture, Architecture

Teaching Experience: 14 years

Experiential Learning in a Design Studio, Student engagement in a lecture course.

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, Lab Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Experiential Learning, Discussion Facilitating

Teaching Philosophy

As a faculty member and now administrator, I facilitate a reciprocal dialogue between educational, professional practice, and industry while promoting student and faculty success beyond the classroom. As a twelve-year architectural educator with seven years of professional experience ranging from architectural offices in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Atlanta, Georgia, and Sydney, Australia, I actively encourage each student to think creatively and critically about design, the ground, and the space within the architectural discipline.

My approach is teaching, and student success has not changed. Architectural design is fundamentally about designing spaces through creative problem-solving. Traditionally, the practice and education of architectural design are taught using a project-based method in a studio or lab environment. In the studio, under the guidance of the instructor students test ideas while generating and evaluating alternatives to ultimately formulate ideas into buildings. This is often referred to as the apprentice model, which is rooted in collaboration between professional practice and the academy. The studio environment establishes a foundation that young graduates take to the profession. Therefore, balancing design education with the skills required for success in practice is something every faculty member must negotiate. With this in mind, my teaching philosophy aims to facilitate reciprocal dialogue between educational and professional practice while promoting student success beyond the classroom.

Educational Leadership: Student Success Beyond the Classroom

My educational leadership encompasses two categories: establishing and coordinating the SGH + Dri Design student scholarship/award, and publishing papers on the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL) in journals and conference proceedings. In these categories a sustained record of excellence will be demonstrated with a primary focus on facilitating reciprocal dialogue between education and professional practice while expanding learning beyond the classroom.

The ACSA, AIA-Nebraska, the University, and the College of Architecture recognized my curricular efforts by awarding me the 2022 Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Practice and Teaching Honorable Mention Award (co-authored with Mark Bacon), 2021 AIA-Nebraska Architectural Design Educator Award, 2020 UNL Annis Chaikin Sorensen Award for outstanding teaching in the humanities, the 2019 Faculty Award for Excellence in Teaching for a meritorious and sustained record of excellence in teaching and innovation related to a teaching program, and the 2017 Hawthorne Distinguished Faculty Award for significant contribution to the overall development of the College of Architecture, UNL or its programs.

Deepak Keshwani

Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Programs, Biological Systems Engineering

Teaching Experience: 13 years

Team-based learning, First-Year retention and student success, inclusive teaching practices

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Encouraging Academic Honesty, Inclusive Teaching, Group Work

- Integrating retention and student success initiatives in the First-Year classroom

- Using CATME to facilitate team-based learning

- Current exploration: Systems-thinking and modeling as a learning tool, promoting a culture of academic integrity

- Current challenge: Assessment of in-class activities

Fabio Mattos

Associate Professor, Agricultural Economics

Teaching Experience: 16 years

Experiential Learning

Key Interests: Experiential Learning, Online Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Lecture-Based Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Assessing Learning

I have been teaching for about 15 years, initially during my PhD program in the University of Illinois and then as a faculty member in the University of Manitoba and University of Nebraska. During this time, I have also had the opportunity to teach short courses in the University of Sao Paulo. More details about my teaching experience are listed at the end of the document.

My general approach to teaching is based on two points. First, it is important that students realize that they are taking the course to learn something and that teachers are there to help them learn. Students should feel that they are working together with teachers, not against each other.Therefore, students need to feel that teachers are happy to be there, willing to help and excited to see students progressing through the course. For example, I often share with students things that I like to do and stories about my life as they fit in our conversations or discussions in class. I don’t force it, but rather let it happen naturally. I also check in with students regularly, especially the ones that don’t come to class often, are missing assignments or have poor grades. In these situations, I reach out just to let them know that I am interested in their learning and want to know how I can support them.

Second, I believe that we all learn more effectively when we enjoy what we are doing and can apply what we learn to real-world events and problems. Commodity markets are the general background in all my courses, so I always design discussions and assignments based on current events in commodity markets. We talk about what is going on in the markets and use what we are learning in class as the lead. In assignments, for example, I ask students to explain why a certain event is happening in commodity markets and what the implications will be. I also prepare simulations in which students take the role of a farmer (or a market analyst, or a commodity trader) and have to make decisions about buying or selling commodities using what they are learning in class.

Several topics interest me in teaching. Currently, I am especially interested in the following. All my courses have two sections. One is in-person and the other is online. So I am constantly thinking about these two delivery methods and how students can learn effectively regardless how they take the course. In addition, I have been thinking about ways to improve learning assessment, engagement and grading.

Debbie Minter

Associate Professor, English

Teaching Experience: 31 years

Writing to enhance active learning

Key Interests: Encouraging Academic Honesty, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Group Work

I honestly don't know that my pedagogical approaches are unique but I do have a lot of experience using/teaching writing in the college classroom. The classes I teach are typically ACE 1 (required vs freely chosen). So I have developed some strategies for working with reluctant writers as well as writers who struggle with the work of writing. Writing is both a tool for organizing and reflecting on new knowledge (as well as our inner thoughts) and it is also a product that is sometimes judged according to disciplinary standards. So it is important for us as teachers to have a sense of why we are assigning it and what we hope students will take from the work of the assignment. To save ourselves time and energy, I argue for focusing our response-work on the learning we want to see. There are response strategies that minimize the time a teacher must spend with each individual piece of writing. Sharing some of these strategies might help more teachers use writing in their classrooms across campus and help of us to develop together additional new strategies. I'd really like to be a part of that!

Jennifer PeeksMease

Assistant Vice Chancellor of Inclusive Leadership and Learning, Office of Diversity and Inclusion

Teaching Experience: 20 years

Inclusive Classrooms and Curriculum and Community Service Learning

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom, Experiential Learning, Group Work

My teaching experience spans one high school and six institutions of higher education. I'm particularly skilled in strategies and tactics for creating inclusive classrooms and experiential learning activities (including community service learning). I focus on both small shifts and habits that can enhance inclusivity and student engagement, as well as attending to the semester long arch in terms of building relationships toward the goals of engaging challenging topics and fostering a willingness for vulnerability that allows for meaningful growth.

Vish Reddi

Assistant Professor of Practice, Construction Management

Teaching Experience: 7 years

Built Environment, Engineering, Architecture

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Inclusive Teaching, Online Teaching, Experiential Learning

Construction Management, Industrial Systems in Facilities.

Greg Simon

Associate Professor of Composition/Jazz Studies , School of Music

Teaching Experience: 11 years

Creative exploration in individual/classroom settings, alternative assessment strategies, project-based pedagogy, empowering novice learners

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Lecture-Based Teaching, Inclusive Teaching, Encouraging Student Agency in the Classroom

I have taught in virtually every setting the School of Music offers, including lecture-based classes, one-on-one lessons, and ensemble learning. My special interest in developing teaching strategies applicable to not only professionals-in-training but novices and first-time learners has allowed me to reach a broad spectrum of students, from nonmajors to graduate students who have won awards for their artistic work. I have published writings on teaching in the College Music Symposium and the Oxford Handbook series, and in 2020 was the Hixson-Lied College Curriculum Development Award.

Rob Simon

Associate Professor of Practice, Marketing

Teaching Experience: 19 years

Experiential and application oriented teaching, connecting classroom experiences to industry experiences, and case-based teaching.

Key Interests: High-Enrollment Teaching, Experiential Learning, Discussion Facilitating, Group Work

I am very focused on experiential and application oriented teaching. I come from a business background and I want to bring that experience into the classroom. In my smaller classes I have student work with real clients on real projects or problems. I also use numerous cases in those classes, because they can to some extent mimic the business and managerial experience. In these smaller classes my role is a facilitator and coach as well as a teacher. I am interested in what the students learn today that will apply in their career 5 years from now.

I try to make my smaller size classes as experiential as possible. I have and continue to work with businesses, non-profits, and NGO's to bring that real world experience into the classroom. I have developed a relationship with businesses in Lincoln and Omaha to where I now facilitate special classes where the students work directly with some of these organizations in project based classes. I also try to focus on giving my students the interest in life long learning. It is not just what you learn today, but how you become a lifelong learner.

Leen-Kiat Soh

Professor, School of Computing

Teaching Experience: 22 years

Computational Thinking, Introductory Computer Science, Problem-Based Learning, Teaching Using Games

Key Interests: Discussion Facilitating, Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Lecture-Based Teaching, Experiential Learning, Group Work

- Active learning with in-class group work, engaging topics.

- Use of technology and games

- Use of insights about our daily activities to prompt students to reflect and apply

- Understanding of the growth mindset and encouraging students to adopt that mindset

- Understanding of student learning strategies and learner profiles and identifying patterns and behaviors to detect and mitigate

I have published quite extensively in CS education research as well as in self-regulation and motivation.

Roberto Stein

Associate Professor of Practice, Finance

Teaching Experience: 13 years

Technology (Canvas, video tools, advanced PowerPoint, etc.); course design; cheating prevention and detection

Key Interests: Assessing Learning, High-Enrollment Teaching, Teaching with Technology, Online Teaching

I've taught almost every type of course imaginable, including large and small sections, online and classroom, graduate and undergraduate. Over the years I've learned a lot about effective course design, be it by participating in UNL's "Peer Review of Teaching" program, or working with UNL's Instructional Designers to develop new courses. I like to combine a good design approach with technology solutions that make life easier for both, students and instructor, while keeping the overall cost and complexity of the tools used as low as possible.

Jessica Walsh

Assistant Professor, Editorial (News-Editorial)

Teaching Experience: 11 years

Ice-breakers & engagement activities; community building; mastery grading

Key Interests: Experiential Learning

Some strategies I use include ice-breaker and engagement activities to start each in-person class and build community. I believe students learn better when they feel safe and part of a community. I also believe in giving short lectures, followed by in-class/peer-to-peer work applying those concepts followed by an at-home graded assignment. Finally, I allow lots of rewrites in my classes that are usually graded at full credit and not averaged with a previous grade to give students a chance to learn from their mistakes without it hurting their grade.

I want my students to do hands-on work in the classroom - this is not unique. I also try to link what we are doing in the classroom and homework to scenarios and dilemmas they would face in internships and jobs - so they can see how they'd use the skills they learned.

Some innovations I've recently employed: Including video interviews with working journalists and editors where they discuss common problems they encounter (these are linked to a short quiz); creation of TikTok-style videos in class to demonstrate knowledge and build community; assignment to find someone in their future field and write about them (great for networking!); "mental gymnastics" like playing Wordle, Spelling Bee or other language-based games to start class.

Jiangang Xia

Associate Professor, Educational Administration

Teaching Experience: 16 years

Online teaching of applied quantitative research methods and related courses

Key Interests: Teaching with Technology, Lecture-Based Teaching, Online Teaching, Experiential Learning

To support student success is the goal, and I support students from several aspects. Learning quant methods online is challenging, however, I believe I have figured out a way that has turned the challenge into advantages. Traditional in-person quant methods courses are challenging as well for many graduate students, and unfortunately I was one of them. The challenge is students can't remember the content after class and there is no way they can retrieve the teaching. But for online teaching, it is possible. In my courses, I recorded step-by-step lecture videos and uploaded to Canvas. Students found my videos the most helpful to them and many of them told me they watch the videos several times to learn the content and complete the homework assignments. This "re-watchable" feature of online teaching goes beyond the traditional in-person classes and it is particularly applicable for learning quantitative methods. Besides, to support students, I also offer optional live sessions so students can come to chat and ask questions. Student found that very helpful as well. My third approach is to ask students to work on a two-or three-draft final project that is based on their own interest. Students found this assignment very engaging and beneficial. Additionally, I offer some students individual meetings and adapted assignments to accommodate their unique situations or challenges. For example, one student has already failed one quant course previously. And she came to my course since she wanted to give it a second try before she gives up with our program. I realized my course could make a difference in her life. So I have met with her multiple times and offered her feedback of her assignments and offered the revision opportunity. I hold the belief that the grade is not the goal while students actual learning is. So I do not mind giving students the second or third chances if they are willing to take it. This student is one of them and she made it through and now she is able to continue with her dream of earning her doctoral degree. As an instructor, I am really happy for her.

Jing Zhang

Assistant Professor, Biochemistry

Teaching Experience: 11 years

Course-based Undergraduate Research Experiences (CUREs)

Key Interests: Lab Teaching, High-Enrollment Teaching, Experiential Learning

I began to adopt CUREs into biochemistry lab courses in 2016. Compared to the traditional cookbook-style lab, CUREs incorporate key elements of faculty research into lab courses to give all students enrolled in the course an opportunity to experience the process of scientific research. This is an inclusive and high-impact pedagogy because research experiences improve student outcomes including retention and persistence in STEM, especially for students from underrepresented minority groups. I am currently serving as one of the faculty mentors in an NSF-funded CURE national network that involves different types of institutions including community colleges, minority-serving institutions, primary undergraduate institutions, and research-intensive institutions. I want to continue to use my experiences and expertise to provide students an inclusive and equitable quality education in Biochemistry and beyond.

Flexibility: What to consider in attendance policies

Choosing an attendance policy that will work for your particular course and teaching style can be tricky. There are many different options available, and how well each works will depend on factors such as the discipline, course level, enrollment size, and instructor educational philosophy.

This page is designed to help you think about the different options and how they might fit with your needs. It contains a variety of examples of late work policies, annotated with things for you to consider before adopting that policy type. While this page may seem lengthy, it’s important to remember that good teaching is hard work! To support students equitably, it is critical to think about the implications for your syllabus policies on different student populations.

Before you dig in, know that this is not intended to be an exhaustive list - there are other creative options available for crafting great syllabus policies. It is also possible to mix elements of the different approaches together if none of them feel like quite the right fit. Note that these are focused on how attendance factors into the grade. It does not examine options like providing recorded lectures or Zoom options for students that might miss class, although those are important considerations that may affect which policy instructors decide to implement.

Options for how attendance is calculated into the final grade

- Attendance counts as a specific number of points or percentage of the final grade, with the attendance grade dropping for every class missed after a specific number

- This is one of the most common types of policies, and it is easy to implement in a variety of situations. Giving all students a specific number of absences without needing an explanation provides some level of flexibility, but students in specific situations (having a disability, encountering an emergency situation, having family and/or work obligations, etc.) may need flexibility beyond what is available.

- Attendance is not directly factored into the grade, but the course grade drops for every absence after a specific number

- This is another common type of policy, but tends to be more punitive than when attendance is factored in as a percentage of the grade. This type of policy can therefore make grading even more inequitable for students with disabilities or those experiencing other emergency situations.

- Attendance is not taken or there is no grade impact for missing class

- This provides a lot of flexibility for students that need it, but also removes accountability for students coming to class. This can result in lower grades and high levels of student disengagement since students often overestimate their knowledge of the subject and ability to complete assessments without attending class.

- Attendance does not account for a specific portion of the final grade, but absent students miss out on in-class activities that are worth points.

- This type of policy ensures that the grade is for student engagement or learning rather than just showing up to class. If paired with an opportunity to complete those learning activities outside of class for students that are absent, this can be a good way of encouraging attendance while providing flexibility. However, it can require more time from the instructor depending on the type of assignments taking place and whether / how make-up opportunities are handled.

- After a specific number of absences, students are required to attend a meeting with their instructor and/or advisor. This may or may not be paired with a grade penalty.

- This policy signals to students that the instructor (and perhaps others at the university) are available to provide support. The conversation allows students to explain reasons for absence and in response, the instructor and student co-create a pathway forward. This type of policy works best for relatively small courses within a major, but could be adapted to other situations.

- Allowing students to help co-create the attendance policy

- Allowing students to help co-create key parts of the syllabus like the attendance policy can help give them ownership and buy in for the process. However, it can be difficult to find a process that achieves consensus without some students feeling unheard.

Options for Excused Absences

- Must provide documentation

- It is common for instructors to state in the syllabus that they require documentation for any excused absence. While this works well in some situations, it can put a difficult burden on students and in some cases, is impossible. For example, students may have COVID or another severe illness without visiting a medical provider. To meet this requirement, you are therefore asking students to make a medically unnecessary trip to a health care provider that could be expensive and may be difficult for students that use public transportation. Even if students go to a medical provider, the facilities don’t always provide documentation to students that go to appointments. Requiring documentation can therefore result in students not being excused when they should, or even encourage them to come to class when sick.

- Any absence is considered excused as long as they contact the instructor

- This type of policy tries to be as flexible as possible with the definition of ‘Excused’ absence. Policies like this avoid the documentation issues described above and also remove the burden of determining whether an excuse is valid or not. However, there are some students that still find contacting the instructor to be burdensome and end up losing points, and there may be some students that end up falling behind because they use too many excused absences.

- No excused absences

- This type of policy is usually paired with having a specific number of allowed absences before losing course credit. Policies like this are easy to implement and avoid instructors having to determine what ‘counts’ as an excused absence. However, while this gives some level of flexibility, it may not be sufficient for students in some situations, which can lead to students being penalized for having a disability, being sick, or having family or work obligations.

Additional considerations when crafting attendance policies:

Create a policy you can follow. Often, faculty will craft strict policies with harsh penalties that they don’t follow (for example, they will allow excused absences in some situations even though the syllabus says otherwise). This disadvantages any student that takes you at your word and doesn’t ask for flexibility that may be available. 1st generation college students and those of marginalized backgrounds are more likely to believe exactly what you write in your syllabus, which causes inequity if you don’t follow your stated policy.

Avoid just linking to the university’s policy. The university policy is not specific about how many absences are allowed or how absences will impact your grade. It mostly contains language about what instructors are allowed to implement as policies. Just linking to the university policy can therefore leave students confused about what the rules are in your particular course, and they may make the assumption that it’s the same policy they’ve experienced in other courses.

Be clear about why you want students to come to class. One of the easiest ways to encourage students to show up is to explain why you value them being in class. Maybe it’s that students historically perform better if they have higher attendance, or maybe it’s that you value hearing everyone’s voice in your discussions. Whatever your reason, let students know why you value them being physically present.

Balance student wellness (COVID-19, flu) with wanting students in class. We know it’s important for students to be in class, but it’s equally important that they stay home when they’re not feeling well to avoid spreading illness to other students. When writing your policy, use language carefully to make it clear that while you value students being in class when possible, you also value their safety and wellbeing.

Consider using a form to track absences. One of the biggest challenges instructors face regarding attendance is keeping track of excused absences. Sometimes this can be done in the Canvas, but if not, setting up a form that asks students for information like ‘name, date of absence, reason for absence, etc.’ can take those conversations out of your email inbox into a space that’s easier to track.

Avoid using harsh language. Whatever policy you choose to implement, pay close attention to the language that you use. Try to write it in your own voice as an instructor, and be sure to explain the reason you chose that policy. When you use all caps and bold font to say ‘DO NOT’ do something, it can signal to students that they don’t belong and can’t succeed in the course. Even if your policy includes penalties, find a way to phrase it in a way that signals you support student learning.

iClicker Cloud for Attendance

iClicker Cloud is a student response system used to increase engagement, particularly in large-enrollment courses. With iClicker Cloud, there is no charge to students or instructors to use the system for taking attendance. Learn more about iClicker Cloud on the Academic Technologies website.

How to decide when to be flexible

Kathy Castle, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Practice teaches large-enrollment courses and aims to be empathetic, consistent, and equitable, but it doesn't mean "anything goes."

Instead, she has created a decision tree that helps her meet her goals. Take a look and see how it might assist you in implementing flexibility in your course.

Support Transgender and Non-Binary Students

Transgender Day of Visibility on March 31st is an annual celebration of the contributions of transgender and nonbinary people while also acknowledging the ongoing challenges they face. As an instructor, we encourage you to think of ways that you can better support your transgender and nonbinary students. Some things that you might consider incorporating into your courses include:

- Provide flexibility. The introduction of anti-LGBTQIA+ legislation at the national and state level can have a significant impact on the mental health of impacted students. Providing flexibility in attendance and due dates without requiring documentation can reduce stress and allow students to complete their course work when they have the energy available. This course policy resource guide provides examples of course policies with different levels of flexibility.

- Share your pronouns and respect students' pronouns. On the first day of class, share your pronouns when you introduce yourself. Include your pronouns online wherever your name appears, including in your email signature, Firefly, and Zoom. Provide the opportunity for students to share their pronouns but do not require them to share. Students may be questioning their gender identity or not feel comfortable sharing their pronouns with all of the people in the class. For more information on best practices related to utilizing students' pronouns in the classroom and gender-inclusive teaching more broadly, see this resource from Vanderbilt University.

- Do not make assumptions about students’ gender identity or sexual orientation. Do not assume that students are cisgender and heterosexual. Also, do not assume that students who look a certain way are part of the LGBTQIA+ community. Avoid using gendered language when referring to students (e.g., ladies and gentlemen, guys, etc.) because you could misgender students or make some students feel excluded.

- Briefly apologize if you make a mistake and move on. If you misgender someone or make an insensitive comment, briefly apologize as soon as possible and move on and work to not make the same mistake in the future. Extended apologies or processing your own feelings about your actions can further burden the people impacted by your words or actions. The best apology is changed behavior.

- Connect students with support. Include links to the LGBTQA+ Center, the Chancellor's Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, and Counseling and Psychological Services in your syllabus. Provide a link to the Gender Inclusive Restrooms Map or include where the nearest all-gender restroom is located for in-person classes.

Conceived by Monica Helms, an openly transgender American woman, the Trans flag made its debut in 1999. The light blue and light pink are meant to symbolize the traditional colors for baby girls and baby boys, respectively. Meanwhile, the white hue is meant to represent members of the movement who identify as intersex, gender-neutral or transitioning. According to Helms, the flag is symmetrical, so 'no matter which way you fly it, it is always correct, signifying us finding correctness in our lives. Source: Outright International.

Flexibility: What to consider in late work policies

Choosing a late policy that will work for your particular course and teaching style can be tricky. There are many different options available, and how well each works will depend on factors such as the discipline, course level, enrollment size, and instructor educational philosophy.

This page is designed to help you think about the different options and how they might fit with your needs. It contains a variety of examples of late work policies, annotated with things for you to consider before adopting that policy type. Some also contain ideas of situations where that policy type might work well. While this page may seem lengthy, it’s important to remember that good teaching is hard work! To support students equitably, it is critical to think about the implications for your syllabus policies on different student populations.

Before you dig in, know that this is not intended to be an exhaustive list - there are other creative options available for crafting great syllabus policies. It is also possible to mix elements of the different approaches together if none of them feel like quite the right fit. Note that these are focused on homework and project type work rather than exams. There are a lot of very interesting ways that faculty account for missed exams or students with low exam scores, but that is beyond the scope of this document.

Types of late policies that we’ve seen:

- Due date listed, no late work accepted under any circumstance

- Considerations: While fairly common, this policy poses huge equity challenges. Although the policy is often justified with ‘this is how things are in the real world’, that’s not actually true - people get sick leave and are excused from work during emergencies. During the pandemic, we learned that students have myriad reasons for needing flexibility because they all have different situations and face different barriers. Importantly, this type of policy is often violated by faculty (meaning they will actually give extensions in emergencies), so it disadvantages students that believe the stated policy and don’t ask for extensions.

- Due dates listed, but no penalty for late work (or sometimes no grade penalty, but students get no feedback or lose the option to re-do work)

-

Considerations: This type of policy offers maximum flexibility for students that need it. However, instructors sometimes find that many students procrastinate too much, which can cause students to fall behind if material builds on itself. It can also be difficult to keep up with grading.

Learning happens by trying something, getting feedback, and improving. Instructors assign work because they believe it will lead to valuable student learning. Removing the ability for students to get feedback or re-do work can therefore take away the main reason you have them do the work in the first place.

When might this work well: Upper level or low enrollment courses with highly motivated students.

- Due dates listed, lose certain percentage per day

-

Considerations: This type of policy is somewhat flexible and pretty easy to implement as an instructor (it can even be automated in Canvas). However, some students may still need exceptions, so this could potentially penalize emergencies unless there is a clear section outlining exceptions to the policy.

When it can work well: This is probably the most common late work policy, and can be implemented in most courses.

- Due dates listed, after that earn a specific amount of credit (like 50%) no matter how late

-

Considerations: This policy works similarly to the previous one, which means there is flexibility and ease of implementation. The main difference is that this ensures a decent amount of credit for completing assignments no matter how late they are, which can encourage students to do the work that we know leads to enhanced learning. It is also less penalizing of students that have significant emergencies.

When it can work well: This can be implemented in most courses.

- No late work, but drop a specific number of assignments with the lowest grades

-

Considerations: This can provide some flexibility, and makes it so the instructor doesn’t have to determine what constitutes a ‘valid’ excuse. It can also be automated in the Canvas. However, students may miss out on learning experiences for missed assignments, so this may not be optimal in courses where material builds on itself and every assignment is important. There may still be some need for flexibility on more than the granted number of assignments for specific students, although this method should substantially reduce the number of exceptions granted.

Where it can work well: In high enrollment courses or classes with a large number of assignments across the semester making it difficult to give feedback on late work.

- No late work accepted, but get a specific number of ‘no questions asked’ extensions (often called ‘Oops tokens’)

-

Considerations: This can be very flexible, and makes it so the instructor doesn’t have to determine what constitutes a ‘valid’ excuse. Also, unlike the policy above where assignments are dropped, here students still get feedback on late work. While there may still be some need for flexibility on more than the granted number of assignments for specific students, this method should substantially reduce the number of exceptions granted.

Where it can work well: This method can work well in most courses, although it does pose the challenge of keeping track of ‘Oops token’ use

- Different policies for different assignment types (exams / presentations / major projects no late work, daily assignments lose X% per day)

-

Considerations: This can allow flexibility in particular situations, and also helps signal to students what you value most. These policies can be more ‘realistic’, since in a lot of jobs, different types of work (like presenting to a client vs independently working on a project) have very different levels of importance. However, these policies can be more complex to write, and require instructors to be very specific about which rules apply when. Also, there will still be some situations where students need flexibility beyond what is stated for that assignment type, so having a clear exemptions policy will be important.

- Allowing students to help build the policies and schedule for the course.

-

Considerations: Allowing students to help co-create key parts of the syllabus like policies and due dates can help give them ownership and buy in for the process. You’ll also be able to avoid dates that are particularly busy for a large number of students. However, it can be difficult to find a process that achieves consensus without some students feeling unheard, and you’re unlikely to find a schedule that works perfectly for all students.

Where it can work well: In small classes or courses within a major where students already have a sense of community.

Common beliefs and practices that can be unintentionally harmful:

Requiring documentation to avoid penalties. This can add a burden to students that are already having a difficult time, which sometimes can result in them taking the 0 rather than trying to get an extension. Students can also have very severe illness (COVID-19, the flu) without getting any medical treatment that would provide documentation. Policies like this often use phrases like ‘legitimate absence,’ which can leave students questioning whether their situation counts. first-generation college students and those of marginalized backgrounds are less likely to ask for extensions than other students in situations like this, which leads to inequity.

Requiring notification ahead of time for extensions. While it’s great to encourage students to let you know ahead of time when they’ll need an extension, making it an explicit requirement for being granted extra time is problematic. The term ‘emergency’ means ‘you don’t know it’s coming,’ and if a student is having an emergency, it doesn’t make sense for them to be thinking about your course. Changing the language to something like ‘Either ahead of time or as soon afterward as possible’ signals to students that it’s still okay to contact you after a due date has passed.

Having a stated policy (like ‘no late work under any circumstance’) that differs from what you do in practice (often ‘just talk to me and we can work something out’). As mentioned above, first-generation college students and those of marginalized backgrounds tend to believe exactly what you write in your syllabus. While some students will ask for extensions with this policy, not everyone will, which creates inequity in the implementation of the policy.

Supporting your policy with ‘In the real world there are no extensions’. Actually, there are. People get sick in the real world and need extensions all the time. It can be useful to think carefully about which types of work are granted which types of extensions in your field, and use that to craft a more realistic policy.

‘If I give extensions, they won’t be prepared for their future careers’. Time / project management is a skill that has to be learned over time. By the time they graduate, we want to ensure they have mastered that skill, but as with anything we teach, it’s not reasonable to hold 1st year students accountable for mastery. There is tremendous variation in workplace culture, so making assumptions about what students will encounter in their future careers can result in gatekeeping rather than support. The question then, is how do we design curriculum to support students through learning time management instead of using it as a reason to push them out?

‘Granting extensions to some students isn’t fair to those that turned it in on time.’ As long as you follow your policy as written, all students are being given the same opportunity for grace. Having a very stringent policy in the name of ‘equality’ is what produces inequity and makes it difficult for students with disabilities or emergency situations to succeed.

Writing a policy using harsh language. Whatever policy you choose to implement, pay close attention to the language that you use. Try to write it in your own voice as an instructor, and be sure to explain the reason you chose that policy. When you use all caps and bold font to say ‘DO NOT’ do something, it can signal to students that they don’t belong and can’t succeed in the course. Even if your policy includes penalties, find a way to phrase it in a way that signals you support student learning.

Having a vague late policy. Sometimes faculty will simply link to a university-level policy or say something like ‘late work will be penalized’. It is very important to write a policy that is specific to your course so students know exactly what to expect. Otherwise, they may make assumptions based on what they’ve experienced in other courses, which may or may not fit with how you implement your policy.

How to decide when to be flexible

Kathy Castle, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Practice teaches large-enrollment courses and aims to be empathetic, consistent, and equitable, but it doesn't mean "anything goes."

Instead, she has created a decision tree that helps her meet her goals. Take a look and see how it might assist you in implementing flexibility in your course.

Timely Tools for Student Success

Before the Term Begins

Improve course accessibility and inclusivity

For a quick list for implementing accessibility in specific programs, visit the CTT Accessibility Resource. Consider using this LISTS Accessibility Essentials Checklist to learn the general accessibility rules that apply across all programs and course materials or go through the asynchronous online NU Accessibility Training course. Accessibility is only one aspect of inclusive teaching. Use the Inclusive Course Checklist to identify ways to make courses more inclusive. An instructional designer assigned to your college can help.Publish the course in Canvas a week before the first day of class

To encourage students to prepare to learn, make the course, particularly the syllabus, initial assignments, and course schedule available to them a week before classes begin. Using Canvas reduces friction for students because it minimizes the number of new tools and systems they need to use and ensures they have tech support if they have any difficulties. You can include a link to the Faculty Senate’s required syllabus statements and remind your students of these policies on the first day of class. This will save space in the syllabus for information specific to your class and it will ensure that students maintain access to current information about the policies and resources described.Welcome students and help them understand how the course will work

A welcome message is part of establishing a positive classroom climate and can help cultivate students’ sense of belonging, a key element in inclusive teaching. It can also kindle excitement for the course material.

A "Getting Started" module is a collection of pages in Canvas that introduce students to the course and their instructor(s). This information, along with the syllabus, helps them know what to expect. In ENGL 270, the instructor, Roland Végső, uses a video to introduce himself and the course syllabus. He also provides reflection questions to encourage students to verify they know essential information to succeed in the course. Végső also gives students a video tour of the Canvas course.

In PSYC 181, Manda Williamson also does a video welcome. Additionally, she uses quizzes to help students be accountable for understanding expectations.

Place your welcome message into a "Getting Started" module—a collection of pages in Canvas that introduce students to the course and their instructor(s). This information, along with the syllabus, helps them know what to expect.

Take a look at these examples and a sample getting started module. Be sure to read the Instructor Notes for more details and how to import a "Getting Started" module template into your course.

This is just one of many Canvas Commons modules you may import into your course to support learning.

Provide students with an orientation to Canvas

Help your students learn to use Canvas by including the Canvas Orientation module in your course. CTT instructional designer, Eyde Olson, maintains this module providing critical information about Canvas and student resources. In a section titled "How do I ..." students can learn how to keep track of their assignments, submit assignments, take a quiz and view results, along with several other common, but essential student activities in Canvas. Other sections address Accessibility and Services for Students with Disabilities, academic integrity, resources, technology tips and requirements, and even tips for success.

This is just one of many Canvas Commons modules you may import into your course to support learning. Search in Canvas Commons under Eyde Olson to import the Canvas Orientation and Student Resources module into your course

Verify that course materials are available to students

Whether you have a single textbook or a wide variety of materials, you'll want to be mindful of ordering processes, deadlines, and cost. For a succinct, but thorough overview of this information, click over to Teaching@UNL and learn more about selecting and ordering course materials.

Indicate on your syllabus what materials are required and what are optional. Confirm that students will have access to all required materials by the first day of classes

Include ACE outcome(s) and signature assignments in the syllabus

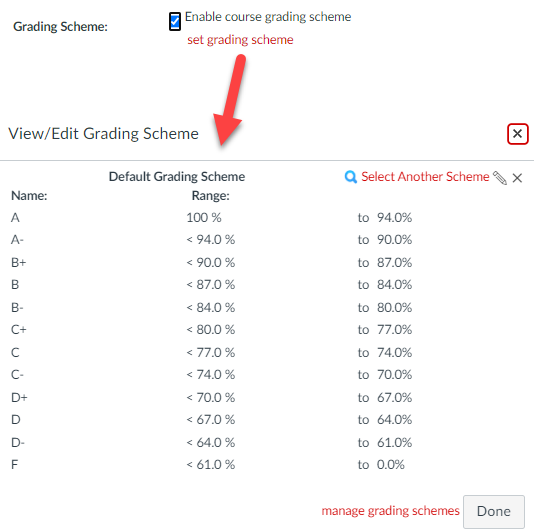

If teaching an ACE course, make sure your syllabus includes the ACE outcome that is met along with the correct statement of the outcome and identify the signature assignment(s) you will assess for ACE. For more details, please see the ACE Governing Document IV: Governance and Assessment.Enable a Grading Scheme in Canvas

The grading scheme in Canvas translates the numeric course grade into a letter grade. Enabling this feature yields two important benefits:

- Allows students to see their letter grade

- Makes it possible for instructors to AUTOMATICALLY import the letter grades into MyRed at the end of the term -- an important time-savings in a large-enrollment course!

Click on Settings > Course Details

Make sure all assignments and quizzes have due dates

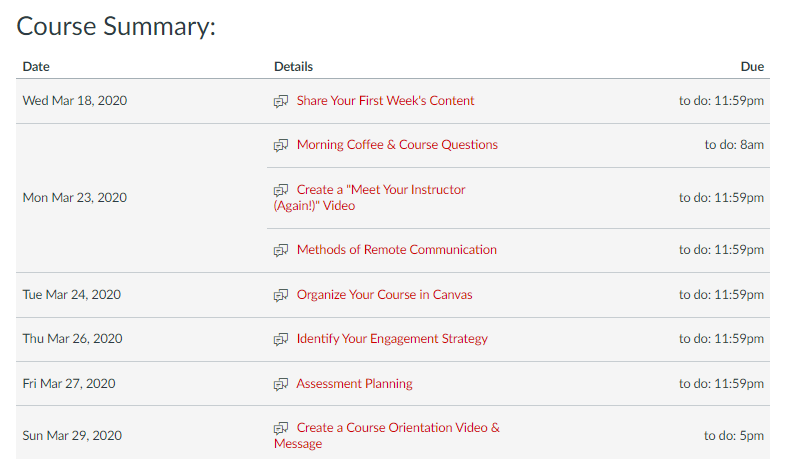

Even if the assignments and quizzes are not yet available to students, giving them due dates helps students organize their term. Moreover, a summary course schedule will be AUTOMATICALLY created on the Canvas Syllabus page. Also, the students in the course will now see those dates in their Canvas calendar that is in the main navigation.

At the Start of the Term

Set the stage for success

Welcome students, orient them to the course, introduce yourself, and share your expectations. For more tips on having a great first week, see "Planning for the first week of classes."Check for gaps in prerequisite knowledge

Prior knowledge checks help you build on students' existing knowledge and know what knowledge gaps may need to be addressed before students can do well in your course. Canvas surveys make it easier to carry out ungraded and anonymous prior knowledge checks. Two ways to check for prior knowledge are performance tasks and prior knowledge self-assessments. Both approaches may pose questions based on what you assume students have already acquired, what you believe is useful to know, and anything else you plan to address in the course.

A performance task could be a quiz with the kinds of questions you might ask on a quiz in your course. In contrast, a self-assessment often uses questions like the following:

How familiar are you with the term "self-efficacy" in the context of teaching and learning?

- I have never heard of it

- I've heard the term but don't know what it means

- I have some idea of what it is, but don't really understand how it applies to learning

- I know what it means and how it applies to teaching and learning in higher-ed

Let students know where to find resources